- Home

- P. J. McKAY

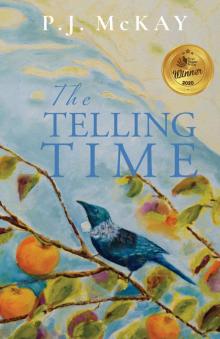

The Telling Time : A Historical Family Saga Page 23

The Telling Time : A Historical Family Saga Read online

Page 23

‘Worth it, though, when you can afford to travel,’ says Mirjana, taking a small bite of her scroll. Mare returns with a pot of coffee and Mirjana pours them both a cup. ‘How’s the trip been? We’ve enjoyed getting the odd postcard.’

‘It’s been amazing. So many cool things.’ Luisa is conscious of gushing. ‘But honestly, this is the best. I’ve dreamt of coming here for so long.’

‘And what’s been your favourite place, Luisa?’ Mare calls out from the stove.

‘So many highlights. But maybe Turkey? Ephesus was incredible and Anzac Cove is momentous for us Kiwis. Turkey was the country that’s surprised me the most, I guess.’

‘Macedonia didn’t rate up there?’ says Mirjana.

Could she be scoffing? Mirjana is probably like Josip and wondering why they even went there. Josip made that very clear: Damned awful place.

‘Not exactly,’ says Luisa. ‘Didn’t help I got sick there.’

‘Tata said you were stressed on the phone. Didn’t sound like sickness. Your friend upped and left, didn’t she?’

‘She did. But these things happen when you’re travelling.’ The nausea is back and she’s desperate to escape upstairs.

‘I wish I could travel like you.’ This time it doesn’t sound accusatory, more a hankering.

‘I used to think New Zealand was the most boring country. Sounds like you might feel the same about here?’ Luisa feels the weight of privilege again. It hadn’t crossed her mind before leaving home, but now she realises how lucky she’s been growing up in New Zealand.

‘Exactly,’ grumbles Mirjana. ‘Only difference is, I’ll never get out.’

‘Macedonia was way behind but I don’t know — here it feels different. It’s just as I imagined from Mum’s stories, but even more beautiful.’

‘Shiny on the surface, but a cesspool underneath. There’s all sorts of rumblings. But we’re used to the conflict. Tito kept things together for a long time, I’ll give him that.’ Her face twists into a grimace. ‘But now it’s unravelling, big time.’

Luisa doesn’t know how to reply. Her imaginings of her Mum’s birthplace had centred on the scenery, the customs and the food, not on how the country was run. In New Zealand she rarely had to worry about politics or how safe the country was. Unless you counted the protests and riots that erupted in Wellington during the Springbok rugby tour in the early Eighties, back when she was seventeen. It would feel trivial admitting to Mirjana that at the time she’d watched Charles and Diana exchange their wedding vows on TV at Niamh’s place and how they’d joked about it afterwards. She sips her coffee, wishing she could offer some meaningful comment. The sinking of the Rainbow Warrior would be the closest thing. But even that had seemed to brush over quickly.

‘Shit happens,’ says Mirjana, cutting into Luisa’s thoughts, her tone matter-of-fact. ‘In this country especially.’

‘We don’t need that language,’ says Mare.

‘And it’s no way to welcome your tata,’ says Josip.

Luisa has been so busy concentrating on saying the right thing that she didn’t hear him come in. She takes in his features again as though seeing him for the first time. He seems years older than Mum. Partly it’s his lined, weather-beaten face but it’s also the way his skin hangs from his cheeks into loose folds around his mouth.

Mirjana laughs. ‘Timed to perfection, as always, Tata.’

‘Ah, wonderful to see you two getting acquainted. Feeling better now, Luisa?’ He stoops to kiss Mirjana on the cheek.

‘Much better, thanks,’ says Luisa.

Josip is beside her now and leans over to kiss her cheek, the brush of his skin like sandpaper. She’s sure he’s about to say something about the phone call. ‘Aunt Mare’s been plying me with food,’ she gushes. ‘And it’s been great meeting my twin cousin finally.’ Mirjana rewards her with a smile.

‘I called your mama this morning,’ says Josip, a concerned expression on his face — a reminder of Mum but with less fire-power. Luisa’s head feels full of static. She’s desperate to know the outcome but at the same time she doesn’t want to hear about it.

‘Jesus. How did that go?’ says Mirjana, looking flummoxed, an expression Luisa imagines she doesn’t wear very often.

‘Mirjana!’ Mare scolds.

‘She says she’ll call back,’ says Josip, his tone suggesting he doesn’t want to discuss it further. ‘Not surprisingly she wants to collect her thoughts. She was perfectly civil.’ He steps forward and rubs Luisa’s shoulder. ‘Mostly she was relieved to hear you were alive and well, Draga.’

‘I’m sorry.’ Luisa pushes back her chair. ‘I feel so rude but I think I need my bed again. A couple of hours and I’ve reached my limit.’ She needs to escape before she embarrasses herself again.

After brushing past Josip, Mare steps forward, blocking her path to the door. ‘From what I can gather the call was short. Gabrijela hung up on Josip. We need to wait now.’ Mare’s expression softens. ‘I hope you sleep well, love. Remember, tomorrow’s another day.’

The stairs are Luisa’s target. She mumbles a quick goodnight and it’s not until she’s halfway up that she feels the stiffness. Each step is a reminder. Worse, though, is the wrench she feels for home. Back in her room it takes her last reserves to get ready for bed. The sad weight of her secret churns and sends up another wave of nausea. It’s like sea-sickness, striking at the most unexpected times. Easier to deal with when she’s alone, when she can reason with herself, parcel it up, and pack it back down. She wonders how long it will be before Mum phones back but even that seems trivial compared to what will be in store if that bastard animal has managed to sow his fetid seed inside her.

SEPTEMBER

Saturday

Two days later, and Luisa has never felt so relieved when there’s blood on her knickers. One more thing that’s gone right, another move in the right direction after all the challenges. She stares at her knickers, at the stain, and despite herself sends up a prayer to thank God.

The previous day she spent holed up in her bedroom to be close to this same toilet. Again and again, the horrors of Macedonia wrested their way to the surface. Kosta using her body. Kosta drilling into her soul. He loomed close even while she was bent over the toilet bowl heaving and retching. In the moments when her body allowed her some rest and she hauled herself back to bed, everything was still impossible, as though she was an empty can, hurtling and twisting along her own muddy river. When she cast her mind away from Macedonia, Mike filled her head. Will I ever put the pieces of myself back together again? Will I ever feel right again in someone’s arms? Making love?

Mare, bless her, was an angel, seeming to know just the right time to pop her head around the door. Thankfully Mirjana and Josip kept away. Without asking questions Mare draped cool cloths on Luisa’s forehead and kept her water glass filled. Later in the day, when it seemed Luisa had nothing more to give, Mare brought dry crackers and a cup of thin chicken broth.

Luisa dresses, making sure to cover her bruise. She stares at herself in the mirror. ‘Okay, first step to rebuilding. There’s nothing you can do about Mum, that’s out of your hands.’ Even so, she pauses at the kitchen door before entering.

Mirjana sits at the table with the newspaper spread out front. The remains of breakfast are on the table: a crusty loaf of bread; a jar of pomegranate jam; a platter of fresh fruit that’s already been well picked over; and a pot of coffee, still steaming. No Mare or Josip? Crossing to the sink she pours herself a glass of water, still unsure whether her stomach will handle anything to eat.

‘Morning,’ says Mirjana in English, glancing up as Luisa sits down at the table. ‘How’re you feeling today?’

Luisa’s relieved to give her a genuine answer. ‘Much better. Seems I might have turned a corner.’

‘That’s good,’ says Mirjana, turning back to the paper. ‘Guess you were sick, after all.’ There’s something in her tone that implies a question.

‘Did Josip a

nd Mare head out?’ says Luisa.

‘Mass.’ Mirjana grins. ‘Tata says he needs all the help he can get.’

Luisa’s sigh escapes more like a whimper and she hides her face in her hands. ‘I feel so bad. Has he heard back from Mum yet?’

‘Hasn’t said. He’ll be fine, though. Think of it as a positive that you’ve got them back in contact.’ Mirjana leans forward, her elbows on the table. ‘We have a saying here. Ne drzite stvari preblizu — and it seems you’re holding things close. When are you going to tell me what happened in Macedonia? And how you lost your friend on the way?’

Luisa groans, her face in her hands. ‘Please don’t ask me about that.’

‘No point letting things fester. It’s our way here. Better to get things off your chest.’

‘I can’t,’ says Luisa, her voice a whisper. ‘Not yet.’

‘Your problems are eating away at you. Then you go and throw them all up, like yesterday.’

‘It’s nothing,’ says Luisa, looking her in the eye. ‘Really. People fall out — you must know that.’

‘But something happened to change things.’ She fixes Luisa with her piercing eyes.

Yes, Luisa thinks, but what about some respect for my privacy? But she feels torn. Mirjana seems more open, warmer, and Luisa wants to build on this sense of camaraderie. But then, she thinks, all the problems she and Bex shared made not a scrap of difference.

The front door slams and Josip and Mare’s voices fill the small hallway. Josip appears in the doorway. ‘Ah, Luisa,’ he says, stopping as though stranded.

‘Go on, tell her,’ says Mare, pushing him from behind. ‘Get it over with.’

Josip hesitates. ‘Luisa. Your mama rang last night when you were asleep. She’s coming in a few weeks. Their flights are booked. Roko’s coming too.’ He pads across the room and squeezes Luisa’s shoulder. ‘Everything will be fine, Draga, I promise.’

Luisa turns to face him, tears pricking her eyes. Everything feels hopeless, out of her control.

‘You are naša, Luisa, one of our own, one of our branches. Our home is your home.’

Goosebumps travel down Luisa’s spine. Josip has just put into words what she has so often failed to encapsulate herself: why she was so determined to come, to reconnect, to understand her origins and pay tribute. New Zealand will always be Luisa’s home but it was in Yugoslavia, Dalmatia, where the roots of her tree first took hold, setting anchor in this inhospitable soil. Even though the limbs of that tree have been far-reaching, she is still one of those branches. This place is what sets her apart.

GABRIJELA, 1958

Korčula, Yugoslavia

MARCH

There was a whiff of celebration, the unmistakable tang of fresh meat, that greeted me when I wound up the hill towards home. I wondered if our neighbours had been spying, if they had noticed the comings and goings in preparation for our important guest. For me, the clock at Jadranka had ticked at half speed all day, torture after enduring a February that seemed determined not to roll into March. I tiptoed inside the house and the aroma was intense, as though it had wafted through each room to find every nook and crevice to settle in. I huddled in our tiny entrance way, straining my ears, feeling furtive but determined to hear him speak. Mama’s laughter filled the house like a song and when his voice finally came it wasn’t authoritative or officious, the way I had expected a Party official might sound, but deep and gentle.

I took extra time washing away the sardines before creeping upstairs to change. Meeting my mystery ujak was definitely an occasion for a dress and I had laid it out on the bed that morning. March was still too chilly for no sleeves but this was my only dress, discounting my ball dress — a tragedy because most of the beautiful golden colour was now covered by my old grey cardigan. I tried to keep my feet light while descending. Mama was always scolding, Walk like a lady, not a donkey, and I wanted to ensure it was me who caught the first glimpse of Uncle Ivan and not the other way around.

‘Gabrijela, moja, is that you?’ Mama called out, before I’d even made it to the bottom step.

I cursed myself as I paused at the kitchen door and smoothed the skirt of my dress. I pushed the door open and peeked around the corner. Uncle Ivan sat in Tata’s seat at the head of the table. He glanced across and smiled.

‘Ah, Draga, moja,’ Mama turned and beckoned me over. ‘Come. Meet your uncle.’

My first thought was how handsome and important he looked. How his smile was at odds with the stiffness and formality of his uniform.

‘Please, call me Ivan,’ he said, scrambling to his feet. ‘Surely I’m too young to be your uncle?’

He looked so sure of himself and his bright white uniform seemed too stark for the room. Despite all my efforts I felt shabby. His hair was even blonder than Mama’s and where her curls were flyaway, his cascaded back in thick waves from his tanned face. I wondered how he’d managed to escape our winter. I shook his hand and he wrapped his other hand around mine. His skin felt soft and smooth not calloused and angry like Tata’s from his work at sea. It dawned on me that I had no concept of what a Party official might be required to do. He reminded me of the officers from El Shatt, and Tito himself, men on a pedestal who were not like our local men. Men you implicitly trusted to deal with important matters, whatever they were.

‘What a treat to meet you again.’ He turned to Mama, ‘Our family produces fine-looking women, Ana.’

Mama giggled like a silly schoolgirl. ‘The younger generation, at least.’

Ivan’s eyes glistened green like shiny olives. I wondered how he saw me. My hand was still in his and time felt suspended. He scrutinised my face. I didn’t know what to say or where to look so I glanced at the floor, worried that my embarrassment might be reflected in his polished black shoes or that my stomach might grumble from the smell of the meat.

‘The last time you were just a baby,’ he said, finally dropping my hand. ‘I think you’ll be more interesting this time.’

Mama came close and wrapped her arm around my waist. ‘Ah, Jela. You were tiny but very noisy.’

‘You wouldn’t stop screeching,’ said Ivan, his grin full of mischief. ‘Josip and I nicknamed you “the seagull”. We were happy to leave you inside with the adults while we rushed outside to climb trees.’

Why was I so tongue-tied? My armpits felt steamy and I was certain my cheeks were as red as apples. It was infuriating that my body played such rude tricks on me but his youthfulness had caught me off-guard. It seemed inconceivable that he was twelve years older. He might as well have been the same age as Josip, he looked so fresh-faced.

‘It’s a crime you didn’t get to know your baba and dida,’ Mama said, squeezing me tight before stepping away and making the sign of the cross. She held her hand to her heart. ‘God bless their souls.’ Her eyes welled and I worried what Ivan might think.

‘A shocking time.’ Ivan frowned. ‘Ana, I apologise for keeping my distance. It was my way of coping. I realise now how wrong that was. You are all the family I have and I appreciate having a second chance.’

‘New beginnings,’ said Mama, looking towards the kitchen as though wanting to escape this talk of family. ‘Come help me, Gabrijela. And after your long trip, you must want to relax, Ivan. Why not take a bath while we prepare dinner. The water’s heating.’

‘Exactly what I need,’ he said. He followed Mama into the kitchen, his smart black shoes tapping against the tiles like a victory march. When he pulled the door shut I joined Mama in the kitchen, for once not resentful about helping her. I tilted my face over the large pot on the stove that was still steaming. The smell of meat was reason enough to stay put. Stacked at the side, on the butcher’s block, was a tray of njoki.

My mouth watered again. ‘He brought us the meat, Mama?’

‘One of the perks of his position.’ Mama smiled. ‘Hopefully there’ll be more in the months to come. Why don’t you help me slice these tomatoes. If there’s still time, you can use the bath w

ater after Ivan. Apparently he’ll be staying at least nine months, plenty of time to get to know him.’ She returned her focus to the tomatoes, seeming lost in thought.

I squirmed. I hadn’t thought about the downsides of having Ivan to stay. I’d had to make the same adjustments when Mare first came and in the past weeks, since she and Josip had moved out, I’d got accustomed to the luxury of having the first bath. I resigned myself to adapting again.

Later, an air of anticipation intermingled with uneasiness swept through our kitchen and dining room. The preparations for dinner were complete. All that remained was for Ivan to join us. He hadn’t re-emerged after taking his bath, and we assumed that he must have important Party business to attend to.

Mama now had a smear of pink on her lips, and she’d changed into the blue blouse and skirt that she always wore to the local dances. Mare had arrived, dressed in her honeymoon outfit — a red skirt and cream blouse — and I was struck by how pretty she looked. Her cheeks were glowing through her powder. I wished I had cosmetics of my own, but Mama insisted I was too young. If Mare had still been living with us she would have powdered my face just like she did before the local dances. Tata and Josip had changed out of their work gear but only into the trousers and shirts they wore on the weekends. They had already started drinking wine. It annoyed me that they could come in from their day at work and relax. For me there was always more work to do.

The table looked festive with its array of water glasses, wine glasses for the men and serving spoons laid out. Mare and I had set it and while we’d managed to find six matching dinner plates that weren’t chipped, the cutlery was an eclectic mix. Ivan was likely used to fine silver, and no matter how hard we tried we could never compete with that. Tata had raised his eyebrows at Josip when Mama put a small jar packed with rosemary in the centre of the table, but I was relieved we were making an effort for our important guest.

The Telling Time : A Historical Family Saga

The Telling Time : A Historical Family Saga