- Home

- P. J. McKAY

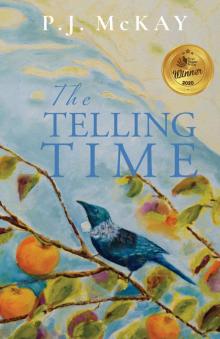

The Telling Time : A Historical Family Saga Page 22

The Telling Time : A Historical Family Saga Read online

Page 22

‘I’m sorry,’ Bex whispers, touching Luisa’s arm and pulling her close. It feels awkward. Staged. ‘I know you’ll be fine, go—’ Bex swallows hard, struggling with her words. ‘Go finish what you planned.’ She kisses Luisa on the cheek, a kiss that doesn’t linger.

Luisa tries to answer but nothing comes out. Now that the moment is upon them her mind races, questioning whether she’s made the right decision. She reaches out, scrambling to hold on to something and catches Bex’s sleeve. But Bex is pulling away and everything feels as if it’s moving in slow motion. Bex bending to pick up her day-pack, backing away, waving — a stiff forced wave — like a small child learning how. It feels so wrong. Bex turning and heading for the departure gate. Luisa watching her go. It’s impossible to tell whether she looks back because Luisa’s eyes have filled with whorls of blurred light.

Upright. Stay upright. Luisa’s backpack lies on the floor beside her and it takes all her willpower not to collapse on it. For now, she must keep a lookout for Uncle Josip. She rocks on the balls of her feet, the tiniest of movements from side to side, wanting to regain some control over her body. Tiny threads of pain still serve as a reminder and she winces, stilling her body, forcing her mind away from all that. It’s back. The worry that her period hasn’t come. Again she rationalises that it’s the stress, all the upset and trauma, of course that’s the reason.

The rain slaps against the terminal windows. All day it’s been claggy, the sky overshadowed with dirty threatening clouds. The lighting from around the building’s exterior reflects inside as a harsh glare. Luisa is mesmerised by the headlamps of the cars swooping in, the soft glow of their amber circles. She thinks about climbing into Uncle Josip’s car soon. How it will be them flaunting their red tail-lights as they crawl away, leaving Macedonia far behind.

Waiting. Waiting. She feels dizzy and so tired, as though Bex’s departure has drained her last ounce of energy. She glances over to the double entrance doors, pulling her jacket closer. For the hundredth time she justifies her decision to stay, ticking off the reasons. Then she sees him. A man wearing a burgundy beret, lingering inside the double doors, scanning the room. He points in her direction and rushes forward, and as he draws nearer she’s reassured by his smile. He’s twirling a small New Zealand flag on a stick above his head. She wants to run towards him but her feet remain stuck.

‘Loo-eeza! Loo-eeza!’ he calls out.

Her legs shake. The man seems worried now. It’s in his eyes and in the arch of his bushy eyebrows. She blinks, trying to focus, but all she can manage is to crumple into his outstretched arms, to stare over his shoulder towards the windows and the lights behind. Why are they so blurry? He’s saying something, but she can’t make out his words. The lights spin as she buckles towards blackness.

When she comes to, her head rings with strange noises. It’s a struggle to open her eyes and she twists her head, this way and that, blinking. Josip’s face comes into close focus. He’s kneeling beside her. She feels so groggy and she blinks again, trying to clear her vision. A woman places a hand on Luisa’s forehead. They are pulling at her from both sides, under her armpits, hauling her up to sit. The woman hands her a flimsy plastic cup and Josip leans in, encouraging her to drink.

‘Popij,’ he says, tipping the cup. ‘Are you hurt?’

Luisa takes a tiny sip, still nauseous, but the thunder and lightning in her head have quietened.

‘Come, Draga,’ Josip says.

Draga. Dida Stipan. Her child-hand enclosed in his giant paw as they collected the fresh eggs from the hen house. Dida’s eyes like warm caramel.

‘Let’s get you over to the side. Away from these crowds,’ he says, a gentle voice. ‘Don’t cry, Draga.’

They’re everywhere. The crowds of people. The lady is talking loudly but Luisa can’t understand her. She seems agitated, tapping Josip on his arm.

‘Do you think you can walk?’ Josip leans in, his breath warm against her ear.

She’s doubtful she can stand but nods. The woman is on her other side, hitching her up under her arms. Josip supports Luisa too and somehow they walk, half-dragging her, towards the bank of windows.

‘Move it, move it!’ says Josip, swishing his free hand sideways at a group sitting on a bench seat.

They scramble to their feet and move away. It’s a relief to slump down. Luisa’s forehead feels clammy and instinctively she reaches for her stomach as her body is racked by spasms. She retches but there seems nothing to bring up. The lady rests her hand on Luisa’s forehead. It takes all her effort to breathe deeply, stop the giddiness. The faded linoleum comes into sharp focus with its deep cuts and dirty scuff marks. The woman mutters something to Josip.

‘My pack,’ Luisa groans, suddenly remembering.

‘Bah! First the precious cargo, then the old knapsack.’ Josip pulls a large handkerchief from his pocket and hands it to the woman.

The woman yells out instructions then dabs the handkerchief against Luisa’s forehead. Someone lugs Luisa’s pack over and rests it against the seat just along from them. All the while Josip sits beside her, rubbing her back. The lady offers her the cup of water again and she manages tiny sips. It takes an age, but the nausea passes. The lady touches her cheek, a gentle fluttering tap. She says something to Josip then waves goodbye and eases away. Luisa and Josip are alone now. The air feels cold at her back.

‘I’m sorry,’ she says, her voice croaky.

‘Ah well, it’s one way to introduce yourself,’ says Josip. His lined face seems etched with concern but he smiles. ‘I was worried, Draga. But you’ve got your colour back now.’

‘I’m sorry.’ Is this all she’s able to say? ‘I’m hardly ever sick,’ she adds trying to sound strong.

‘Bah!’ he says, as though hitting her apology away. ‘Mare will get you better. But there won’t be any detours. I’m taking you straight home. Sorry, Draga, but I hope you don’t mind a long drive.’ Josip sits quietly as though thinking, chewing on his fingernails.

It doesn’t matter how long it takes. All Luisa wants to do is leave Macedonia far behind.

‘There’s something else.’ Josip’s face is stern now. ‘When we get home I must telephone your mama. No arguments.’ He shakes his head. ‘Gabrijela would never forgive me.’

She doesn’t have the strength to answer.

AUGUST

Thursday

Luisa’s head throbs. Would Josip have made the call yet? The question has been rolling over and over in her mind as she’s drifted in and out of a restless sleep. She forces one eye open and glances towards the window. Threads of sunlight slip through the slats. What time is it? Mum would be furious, and her razor-sharp tongue is the last thing Josip needs after the shocks of the past couple of days. She curls herself into a tight ball and cringes. Her surprise phone call. Fainting at the airport, having to make the long drive here — could it be any worse? Luisa knows she can’t hide away despite every fibre of her being wishing she could. Poor Josip and Mare. She scrunches her eyes again, trying to ignore the mess in her head.

Curiosity wins and Luisa eases out of bed. Her sweatshirt lies discarded at the foot of the bed on top of a crocheted blanket, a riot of colourful squares. She cringes at the memory: Mare tugging at her sleeve, Luisa insisting, No, I can undress myself, acutely aware, despite feeling so ill, of the need to hide the gruesome yellow-green bruise on her upper arm. She pulls on her sweatshirt. Her body is stiff but the cool tiles beneath her feet feel refreshing, soothing. At the window, she pushes open a pane and leans forward to unlatch one of the shutters, wincing as she folds it against the house. The salt-laden fresh air rushes in, and Luisa scans over the terracotta roof tiles strutting down to meet the harbour nestled at the bottom of the steep hill. The water is the most intense shade of turquoise. Boats cruise, and much further away, behind them all, the mainland’s sheer mountain backdrop crashes into the sea.

Luisa wonders where Orebić is. The place from where she and Uncle Josip cr

ossed on the car ferry that morning. All she remembers of that horrendous drive is lying on the bench seat, pillow tucked under her head, her fingertips tracing the crackled lines in the leather over and over. Somehow it helped block out the fishy smell that was playing havoc with her stomach. Getting to Orebić, stepping outside, and catching a true whiff of the sea was a welcome relief. The dawn sunlight played on the paintwork of Uncle Josip’s pickup truck, nostalgic, a strange sense of homecoming. The cheerful burnt-orange colour reminded Luisa of the brightly coloured Fun Ho! toy trucks her brother Marko played with as a small boy. But then reality returned and with it, embarrassment: catching Aunt Mare off-guard with their early arrival; retching at the breakfast table; Mare trying to help her undress. Gazing out at this scene, in this country where she’d expected to embrace her culture and feel at home, Luisa feels emptiness, as though she has lost her anchor, been cast afloat.

A flapping noise distracts her. High up to her right an assortment of laundry is precariously suspended. Would it be possible to lean out from one house and pass something to your neighbour across the way? A small gang of children, their voices pitted one against the other, as though filling a bubble of excitement threatening to burst, commands the narrow street leading up from the town. The end of a school day? Luisa has lost track of time. They are all dressed similarly in maroon and white. Has she really slept for most of the day? Despite all that’s happened she wonders how Bex has coped getting to London. Hopes she’s all right. It feels odd not having her here.

Turning back, she takes in the plainly furnished room with its whitewashed walls and muddy-green tiled floor. It’s a comfort seeing her pack propped next to a plain timber chest of drawers. A gilded mirror hangs above the chest and sitting on top, next to a small jar of lavender, is a photo of Baba Ana. Luisa would know those curls and that face anywhere: they have the same photo at home. It’s important to put everything behind her, make the most of connecting with her family. But still the question — what if she’s pregnant? It hangs over her like a black cloud. Music. She plugs the Walkman buds into her ears and Toni Childs bursts inside her head: ‘Don’t walk away.’ How can you not play mind games with these lyrics? On the wall behind the bed is a plain gold crucifix. Luisa makes the sign of the cross — Please, God, help me live with myself again. Keep me strong and my secret safe — but she hasn’t been to church for years. Will God still listen? Does He even care?

The door is pushed open and Mare cranes her head around, ping-pong-ball cheeks and a warm smile. Luisa pulls out the earbuds, switches the Walkman off, grateful she had the nous to cover herself up earlier.

‘Thought you might be ready for some food,’ says Mare. She wears a plain brown house-dress now and a starched white apron splices her squat square-cut figure. Earlier, she’d been hauled out to the street in her dressing gown to help with the luggage. Mare had apologised to Luisa, explaining that she wasn’t expecting them until the following day. Luisa was mortified. Now her aunt’s cheeks are dusted with powder and she wears a smear of lipstick. Mare carries the tray over to the bedside table then bustles across to take Luisa’s hand in hers. That soft skin again, like tissue paper.

‘You’re still so cold, Draga.’ Mare draws Luisa back towards the bed. ‘Come. Have some soup.’

Luisa concentrates on keeping her face relaxed as she climbs back into bed. ‘Thanks. This smells delicious.’ She forces a smile and glances up at Mare, busy propping pillows behind her. ‘I feel terrible. It’s the only time I’ve been sick in all our travels,’ she says, unable to hold Mare’s eye.

Mare passes her the tray. There’s a bowl of brudet, thick tomato-based soup laden with chunks of fish and calamari rings, and a fresh wedge of bread. Luisa still feels wary of her stomach but this soup smells like home. She takes a sip.

‘Delicious! Just like Mum’s.’ She is pleased at how confident she sounds, and that her Croatian isn’t as scratchy as she had feared.

Mare rewards her with a smile. ‘Eat some bread too,’ she says. ‘I made it myself. We need to get you strong again.’ The way she talks sounds like Mum.

Luisa dips the bread into the soup. She hadn’t realised she was so hungry. Mare lingers beside the bed, silent, smiling when Luisa wipes the bowl clean with the last of the bread.

‘Join me in the kitchen when you’re ready,’ says Mare, taking the tray. ‘Take your time.’

Luisa takes a last look around the room. Unpacking and arranging her belongings — toiletries, the small stash of cassette tapes, her book — has felt comforting, another positive step forward. The Swiss Army knife, though, is an imposter and she has returned it to the top pocket of her pack. Any clothes that are still clean are stacked in the chest of drawers and a pile of washing sits to the side. She pulls on a fresh top to cover the bruise then plucks up the courage to head downstairs.

The kitchen is small and cosy with a heady mix of garlic, tomato, onion and meat wafting about. There’s a sweet smell too, and the lingering aroma of coffee. Mare herds her towards a table by the window which looks out to a small courtyard. The sun bathing the table feels inviting.

‘One of Mirjana’s,’ says Mare, pulling a magazine from a cabinet.

Luisa draws the magazine close. A young woman, flawless skin, impeccable outfit, poses before a backdrop of city buildings and a bridge. Paris, perhaps? Luisa wonders if she’ll ever make it there, whether she’ll enjoy travelling again. A plate of scrolls on the table release a warm yeasty aroma mixed with sweet cinnamon. Mare attends to something on the stove and Luisa flicks through the magazine, making out she’s concentrating, wishing she could feel more relaxed.

‘Is Josip still in bed?’ she asks, thinking she should make more of an effort to chat. It’s just as well Mum kept the language alive at home and made her persevere with the lessons at the club.

‘Went down to check on the boat,’ says Mare. ‘Don’t expect him back for a while.’ She smiles and goes back to her cooking. Luisa is grateful for her no-nonsense manner.

The aroma from the cinnamon scrolls overrides everything. Having conquered the soup, Luisa reasons that the queasiness she’s feeling is what always happens just before her period, or perhaps it’s just hunger? Her period’s well overdue but she knows how stress affects her cycle. You’ll be fine, she reassures herself.

There’s a noise in the entrance way and Luisa jerks her head up. ‘Must be Mirjana, home from work,’ says Mare, glancing towards the door.

A young woman stalks into the kitchen. She has the same beanpole frame and olive skin as Luisa. ‘They arrived early,’ says Mare, responding to Mirjana’s surprised look.

Mirjana crosses to the table and Luisa pushes herself to standing. Her cousin is slightly shorter and her face is more angular. It’s her striking eyes which distinguish her: little black beads.

‘The mystery cousin,’ says Mirjana, her thin nose at a tilt. ‘Finally, we meet.’ She hugs Luisa but it’s a brisk rather than warm embrace. Her black hair is sleek and shiny and styled in a short bob, the ends flicking out at chin-level. The way she carries herself, stiff and erect, together with her serious demeanour, makes Luisa think she might have a battery pack strapped to her body keeping her fully charged, that crackles of energy might fly off her.

‘Nice to meet you too!’ says Luisa, trying to sound relaxed. She feels that she’s being sized up and spat out by Mirjana, who offers a half-smile back. If Bex was here, she’d jump in with some banter to smooth the way.

‘What time did they get here?’ Mirjana asks her mum now. ‘Wasn’t it meant to be tomorrow?’

‘Just after you left for work. Poor Luisa’s been in bed most of the day. She’s not well.’

‘Oh? Still sick. What’s wrong?’ Mirjana fixes Luisa with her piercing eyes.

‘Some bug I picked up. That, and a bit of exhaustion.’ Luisa swishes her hand as though batting Mirjana’s questions away.

‘Guess you can’t complain. Not with all that travel.’

‘You mus

t work close by?’ says Luisa, desperate to take the focus off herself. She thinks about her own job and how Mirjana’s got it lucky to be getting home so early — she would be at work for at least another couple of hours.

‘Why don’t you two sit down and get to know each other,’ says Mare. ‘I’ll make some coffee to go with Mirjana’s favourites. Do you have the sweet rolls at home, Luisa?’

‘Yes. I’ve been holding myself back to be honest. They smell delicious.’ Perhaps food is Mare’s language of love too. Mum often says, Love goes through the stomach, linking a recipe back to someone from the homeland: Nada’s Mama’s brudet, or Baba’s jabucni strudel, the dessert she made when apples were plentiful.

Mirjana pulls out a chair opposite. ‘Aren’t you going to join us?’ Luisa asks Mare, thinking how much easier it would be with her at the table too.

Mare pats her shoulder. ‘I’ll be back over soon, Draga. A few jobs first.’

‘Let me help,’ says Luisa, making to get up, the sudden movement sending a jolt of pain. She winces but doesn’t dare look across at Mirjana.

‘No. You rest up,’ says Mare. ‘There’ll be plenty of time later for helping.’ She’s already back at the kitchen bench and Luisa eases herself back down onto her chair.

‘You asked about my job,’ says Mirjana, fixing on Luisa. ‘I’m a paper-shuffler. At the local post office. Not as exciting as being a lawyer, I’m afraid.’

‘Don’t know about that. Plenty of paper-shuffling in my job too.’ Luisa sinks her teeth into a scroll. It’s delicious, sticky and still warm. Her stomach does a cartwheel, but she’s determined not to let it show on her face. When will it settle?

The Telling Time : A Historical Family Saga

The Telling Time : A Historical Family Saga