- Home

- P. J. McKAY

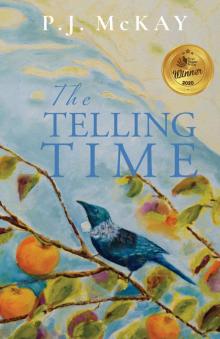

The Telling Time : A Historical Family Saga

The Telling Time : A Historical Family Saga Read online

The Telling Time

P. J. McKAY

Contents

Author’s Note

Gabrijela, 1958

Korčula, Yugoslavia

FEBRUARY

Gabrijela, 1959

Auckland, New Zealand

FEBRUARY

MARCH

APRIL

MAY

JULY

OCTOBER

NOVEMBER

DECEMBER

Luisa, 1989

Auckland & Yugoslavia

JANUARY

APRIL

AUGUST

AUGUST

AUGUST

AUGUST

AUGUST

AUGUST

AUGUST

AUGUST

SEPTEMBER

GABRIJELA, 1958

Korčula, Yugoslavia

MARCH

MAY

AUGUST

SEPTEMBER

OCTOBER

DECEMBER

LUISA, 1989

Korčula, Yugoslavia

SEPTEMBER

Join Team Telling Time!

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Note on Sources

Book Club Discussion Notes

Copyright

First Published 2020. Copyright ©️ P.J. McKay 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. This book and any associated materials, suggestions, and advice are intended to give general information only. The author expressly disclaims all liability to any person arising directly or indirectly from the use of, or for any errors or omissions in this book. The adoption and application of the information in this book is at the readers’ discretion and is his or her sole responsibility.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand.

IBSN 978 0 473 52012 0 (e-book)

ISBN 978 0 473 52011 3 (paperback)

Cover painting by Catherine Farquhar www.catherinefarquhar.art

Cover design by Laura Becker www.laurabeckerdesign.com

Author photograph by Colleen Maria Lenihan

Published by Polako Press www.pjmckayauthor.com

In memory, of Gran, Phyllis Louisa Lamont,

who always said I would.

Children show scars like medals.

Lovers use them as secrets to reveal.

A scar is what happens when the word is made flesh.

Leonard Cohen

Author’s Note

The following family monikers are used throughout the novel:

Tata — Dad, father

Mam — Mum, mother

Dida — Grandad, grandfather

Baba — Grandma, grandmother

Ujak — Uncle

Teta — Aunt

A note on pronunciation:

Č/čas ch(like chalk)

I/ias ea(like east)

J/jas y(like yellow)

K/kas c(like cut)

Š/šas sh(like shut)

The Croatian terms of endearment — Draga (for females) and Dragi (for men) — are used throughout.

Dally (collectively Dallies) — a short-form for Dalmatian, describing the people who immigrated to New Zealand from the Dalmatia coastal region. Mostly an affectionate colloquialism.

Gabrijela, 1958

Korčula, Yugoslavia

FEBRUARY

Sardines. We reeked of them — me and all the other women working at the Jadranka fish factory. Their stinking oil greased up our hair and our skin, and their flesh got wedged under our fingernails. I could taste them at the back of my throat. We sat jam-packed beside the conveyer belts, or on long tables, trussed up in our matching white uniforms and headscarves: preparing the sardines, sorting them and stuffing them into cans. There was no escape and complaining made no difference. I would be trapped there until I got married, and even then it wasn’t a guaranteed thing. Some women never escaped.

My dream was to be a teacher but Tata said working at the factory was more important because I was doing my bit for the economy. Vela Luka and our family fishing business relied on me. Tata and Josip played their part by hauling in the fish on Krešimira, and I stuffed them into cans. My eighteenth birthday, in January, marked eighteen months at that prison. Most of the local girls did their time but that was no consolation. Men rule the roost in Yugoslavia, girls are second best, and throughout my childhood I’d been conditioned not to challenge this order.

All day I’d been stuck with two older girls who chatted between themselves with no interest in talking to me. We had no sooner emptied one tray of the lower-grade sardine chunks when someone loaded another pile on. Our job was to gather up the offcuts and pack them neatly around the higher-grade fillets in the cans trundling past. The offcuts made them look full without being the first thing you noticed. Our supervisor told us the job required judgement and dexterity but to me it required the patience of a saint. My head felt crammed with the clamour of machines, and the din bouncing off the walls and low ceilings rattled inside me. At times I felt it all might escape as a scream.

When the conveyer belts ground to a halt, I ripped off my head scarf, scrunching it into the front pocket of my uniform dress. I searched the room for my friend, Nada. She’d landed one of the better jobs that day, ladling olive oil into the cans before they were sealed. I hadn’t seen Antica; she must have been late arriving. There was Nada, standing at the side, folding her headscarf into a neat triangle. As usual, her short dark hair sat perfectly around her pixie face. She waved and I signalled for her to wait. I never understood how she could always be so cheerful. Nada would never get into a war of words with our supervisors, unlike me. I was always saying things that got me into trouble — the same at home.

I joined Nada and we merged in with the trail of women, all in our regulation flat shoes, all trudging across the wet concrete floor towards the cloakroom. The men, in their rubber gumboots and over-pants, were already wielding their hoses, directing the debris to the sides in preparation for the night shift. I worried they might collect us up as well.

‘Thank God that’s over,’ I said. ‘Where’s Antica?’

‘Got the worst job.’ Nada grimaced. ‘Arrived too late again.’

Poor Antica. She would have spent all day at the first station, scraping off the scales with the razorblade knife. Her fingers and uniform would be smattered with sardine debris. I scanned the cloakroom for her.

‘Had to go early,’ said Nada, scrubbing her hands at the basin. She gave me a knowing look. ‘Her mama was in charge of little Luci.’

I peered in the mirror at my washed-out face and greasy hair. Life was so unfair. ‘That Marin better marry her soon,’ I said. ‘What a toss-up — babies or sardines.’

It was hard keeping the sarcasm from my voice but there was no point complaining to Nada. She got annoyed if I showed too much negativity. The three of us had been friends through school, and it always puzzled me where Nada hid her feelings. She let them out so rarely that sometimes I wondered if I knew her — if she even knew herself. I wished she would take a few more risks, open herself up more, but neither of us wanted to be like Antica. There were downsides to taking a rebellious nature too far.

‘I hope her wages don’t get docked,’ said Nada. ‘That would be the last straw.’

We finished scrubbing our hands and I checked my face again, still feeling unclean but knowing the worst of it would have to wait until my ba

th later on.

‘Come on,’ I said. ‘Let’s scat. We won’t solve Antica’s problems staying here.’

It was drizzling again outside. We were stuck in the middle of winter, February, my least favourite time of the year. Nada pushed up her lime-green umbrella and we huddled beneath it, joining the parade of nylon canopies, colourful contrasts to the grey of the sky and the stark hills looming over the town. I took the handle to make it easier. Nada only reached my shoulders and her legs were like thin sticks. Antica and I often joked that she might blow over in a puff of wind. All the same I envied her petite build. Antica begged to differ. She said men preferred something to hold on to — and she would know. Letting Marin fondle her breasts had led to little Luci.

Around the port there was a bustle of activity, boats coming and going, men shouting orders. I scanned the harbour for Krešimira but couldn’t see her. I leaned in closer, shielding Nada, as we walked briskly away.

‘And will you be seeing Branko tomorrow night?’ asked Nada, glancing up with a sly smile.

‘Depends,’ I said, trying my best to sound candid. ‘And you? Dinko calling by?’

Nada shrugged and laughed. Branko was Nada’s older brother, and she often joked that one day we might be related. We were practically relatives anyway, having all shared a tent at the refugee camp in Egypt. I’d even been there, in that same tent, when their youngest sister, Ruža, was born.

‘Sometimes I wish I could escape all this,’ I said. ‘Do you ever think it’s strange that we lived in Egypt for two years, and yet now we never leave this small island?’

Nada frowned. ‘That was horrible, though. Why would you want to leave? I’d much rather be here.’

‘Just to see. There must be more to life.’

‘You should be grateful for what you’ve got. Who would go back to all that?’

All that. Our camp stretchers lined up along canvas walls. Running barefooted and hiding behind the flapping canvas; jumping and sliding to soft landings in the sand hills on the perimeter of the camp. Mama sweeping and shaking and sweeping again, trying in vain to remove that endless sand. Snuggling against Mama and stealing her heat when the air froze at night. All that, plenty of memories, not all of them bad. Perhaps it was just the sardine factory draining me of any spark. I pulled my coat around me to hide my hideous uniform, hoping we wouldn’t bump into anyone we knew — especially one of the boys.

The evening had closed in, but the oil lamps inside the houses added some cheer. We reached Nada’s street and I handed her the umbrella. The rain had eased to a fine mist, and besides, our house was just up around the corner. It wouldn’t matter if it rained again. I would be washing my hair anyway. It was always my routine at the end of the week; ridding myself of the sardines.

On the last stretch up the hill, I wondered what sort of day Tata might have had. I hoped the fishing had gone well. If the fish were running we were less likely to clash. Sometimes I wondered if he was disappointed I was a girl. That after the eight long years between Josip and myself — three baby boys lost in between — this was his way of punishing me. In his eyes I was nothing more than a helping hand for Mama. He never valued my opinions and I was constantly chasing his approval. Even back when we returned from El Shatt I’d noticed it. Tata was a puzzle piece plucked from my childhood — a piece that wouldn’t fit snugly after our return.

Our house was in darkness except for the blurred light in the kitchen where the fogged-up pane sat ajar. My mouth watered at the aroma of freshly made bread as I shrugged out of my damp coat, cursing when my fingers bashed against the bathroom door opposite.

‘Mama, I’m home!’ I yelled, bursting into the kitchen but stopping short. It was deserted, and the light was so dim that it took a moment for my eyes to adjust. A loaf of bread was cooling on the rack, just to the side of the wood-burner stove. I checked through into the dining alcove.

‘Is that you, Jela?’ Mama’s voice sounded strained. She was sitting with her head in her hands at the table.

‘Are you sick?’ I said, rushing forward and touching her shoulder.

Mama jerked her head upwards. A letter lay open on the table and I peered over her shoulder, trying to see who it might be from. It was typed and official-looking. My stomach churned. It was Mama’s habit to twist and stretch her corkscrew curls whenever she felt stressed or unsure of herself. She stared ahead, the palm of her hand plastered against her face, her unruly mop of blonde curls hanging limp and stretched. It seemed that she might cave in on herself.

‘Don’t be worried.’ She reached for the letter. ‘This stirred up memories, that’s all.’ Her hands were ice-white and trembling. I rubbed her wooden back, still trying to check over her shoulder for clues.

‘But who’s it from?’

‘Ivan, my brother. Half-brother.’

Ivan? We never talked of him. Mama’s family story was complicated. Her tata had died when she was thirteen and just four years later, when she and Tata were engaged, her mama married Dida Novak. Ivan was their son. Both Baba and Dida Novak were dead now, killed in the war. I never got to know them. The last time they had visited I was just a baby.

‘I feel so guilty. I haven’t even visited their graves.’ Mama’s voice was low, as though wanting to hide from the thoughts that were creeping around, shadowing her.

‘You couldn’t,’ I said. ‘It was impossible. And it’s best to remember them by your happy memories.’

‘This letter’s brought back all the horrors.’

I wrapped her in a hug. ‘I’m sorry.’ I didn’t know what else to say. I kept rubbing her back.

Baba and Dida had been killed in the war. Along with Ivan, they were Partisan supporters. Ivan had been away fighting for the cause when it happened. Mama learnt about their deaths while we were in Egypt and when we returned a year later she couldn’t face visiting their graves. They were buried in Split, the place they had made their home, but it was a place that meant nothing to Mama. She always said she wanted to remember her mama on this island, Korčula. Split had always felt foreign to her, just like her step-father.

Mama picked up the letter and folded it back into the envelope then pushed herself slowly to her feet. She was a good head shorter than me now and so, so thin. Tata was always telling her to eat more, but Mama never put on any padding. Her stooped shoulders made her seem older than her forty-seven years, and if it wasn’t for her white apron she might be mistaken for a black stick. People told me I had Mama’s looks with Tata’s hair. I’d also been blessed with Tata’s build and next to Mama I felt hefty, just like I did with Nada.

‘Perhaps light the lamps,’ Mama said, ‘and after you’ve changed you can help me with the dinner. I’ll tell you about the good news then.’

I attended to the lamps in our small lounge and dining room, then made my way up the narrow stairwell taking the stairs two at a time. Ours was a three-storey house and our bedrooms were on the second and third floors: Mama and Tata’s on the top and Josip’s and mine on the middle floor. Josip shared his room with Mare now after they got married last year. It was weird knowing they were both in that room at night, so close, doing who knows what. I’d often hear muffled noises and laughter. It wouldn’t surprise me if Mare escaped the sardine factory soon. I tore off my uniform and changed into my winter skirt and top. Branko and I never touched like that. We kissed, of course, but most of the time it was more a peck. If he ever tried to cuddle me, I always made sure that his hands didn’t wander. It wasn’t just because of what happened to Antica. If I was honest, I couldn’t get past the feeling that I was canoodling with my brother.

Back in the kitchen, it was hard to tell whether the feelings in my stomach were hunger pangs or curiosity. Mama stood by the sink, the envelope now slotted between the slats of the shutter like a red alert. The wind had picked up and the window pane was rattling. I was itching to ask more but I knew better than to rush her. Uncle Ivan was a high-ranking officer in the Party. After all these years, wh

y would he make contact? Mama had tried several times to reconnect after we had returned from El Shatt, but her letters went unanswered. Tata had said to forget him and it seemed Mama had given up. I scratched my brain, trying to remember the last time Ivan’s name had been mentioned.

‘Cut the cabbage, Draga,’ Mama said, washing her hands. ‘We’re back to vegetable stew. Lord knows what Ivan will think.’

I stared after her as she crossed to the wood-burner stove. So Ivan was coming here? A large black pot sat on the stovetop. I knew it would contain her concoction of vegetables and beans for our evening meal. She struck a match to relight the fire.

‘For how long?’ I asked, still trying to make sense. ‘And why now?’ This was the most exciting thing to have happened in years — not only a long-lost uncle but a Party official too.

‘A few months, apparently. He’ll be leading a project upgrading the roads on Korčula.’

I chopped the cabbage. Many of the leaves were yellowed and I scrunched my nose at the sour smell but tried to slice them as thinly as I could. Branko had mentioned this project a week or so back, but I’d only half listened. He was always looking for ways to make money but most never came off. This might be an opportunity for longer-term work, and me having this contact might make it easier for him to apply.

The Telling Time : A Historical Family Saga

The Telling Time : A Historical Family Saga