- Home

- P. J. McKAY

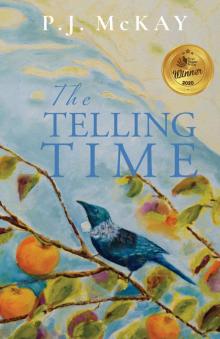

The Telling Time : A Historical Family Saga Page 4

The Telling Time : A Historical Family Saga Read online

Page 4

I followed, but it was the wooden monster my eyes were drawn to. Closer up it seemed even more ungainly. I imagined the Y-shaped arms like semaphore signals sending pleas to the sky. My forehead felt clammy and I turned back to Stipan, envious of his floppy hat. He was standing in the garden, beckoning me over.

‘Only grow the Italian ones,’ he said, cradling a tomato in his palm. ‘Some things I won’t compromise on. And there’s plenty of silverbeet and kupus. Dallies can’t survive without cabbages! You won’t go hungry, Jela.’

That much was obvious. Stipan’s garden stretched the length of the backyard and overflowed with plants laid out in neat rows, so different from our small patches at home. Two black birds with white pompom tufts at their throats swooped low. I followed their flight, watching as they landed on one of the monster’s high lines.

‘Aren’t they beautiful,’ I gasped, squinting my eyes against the sun as they fanned their feathers and whipped away into the trees, their calls tuneful, like songs.

‘Tuis. Native birds,’ said Stipan.

‘But Stipan? That thing. Is it for the clothes?’

‘Bah! That eyesore,’ he said, with a wry grin. ‘Great for the drying. Or so Marta tells me.’

One of the timber beams had ropes tied off like fishing knots and I realised it might work by a pulley system. I hoped what Tata had taught me on Krešimira, might be useful. But how would the clothes dry in this air that seemed laden with moisture? Our winds at home were dry and heavy with salt, the same ingredient we used to draw out the moisture when preserving our meat and fish. My head swooned. It was as though the multiple layers of green, not just from Stipan’s garden, but collectively, from the texture of the surrounding trees and bushes, were crowding in to envelop me.

‘What made you come here?’ I asked, blinking to help stave off the giddiness, cursing Tata again for being so vague.

‘Like everyone. To make a better life. They were calling out for the stonemasons and I knew the craft well, of course. It was 1926. Our Petra was just a baby. Marta’s sister Kate was already here and happy to be our sponsor.’ Stipan’s face clouded with sadness. ‘You know I had to lose my name? Bah! They changed it to Tomich. With an ich! I wouldn’t live anywhere else now, but the homeland . . . it still holds my heart.’

I doubted this place could ever be home, and I vowed to keep a clear picture of my Yugoslavia, the smells and the sounds, to not let those pictures fade. A scramble of clucking and flapping erupted from behind a thatched fence at the far corner of the section.

‘My chickens,’ Stipan said, puffing out his chest.

‘But how do you have time to care for it all?’ I asked.

‘Easy. I retired from the quarry late last year. It was when Marta and I travelled to the homeland. Our first time back. What a shock. But it was incredible to meet up with your tata. We met in our late teens you know, when I moved to Vela Luka for work.’ He patted me on the shoulder. ‘You’ll be missing your family and friends now, Jela, but it gets easier.’

Tears stung again and I turned towards the courtyard. Marta and another woman were looking our way.

‘Ah well, it’s time to meet our Petra,’ said Stipan. ‘Do you remember me pointing out where she lives, on our ride from the airport?’ I shook my head. He had pointed out so many places but they had all blurred into the other. ‘Henderson, remember? Our Hana lives there too. And our youngest, Zoran. I told you, he makes the wine there.’ He strode off, calling out, ‘This is good! Petra, you can meet our Gabrijela.’

His use of my full name came like a jolt, as though all the friendliness we’d just shared was gone. I followed Stipan on auto-pilot, wondering how much else I had missed on the trip from the airport. Petra was a good head taller than Marta and cut a striking figure in her lemon frock patterned with white daisies. It had cutaway arms that complemented her bronzed arms. As Stipan made the introductions I wished I’d had the chance to freshen up. Everything about Petra seemed toned and taut.

‘Nice to meet you,’ said Petra, in Croatian. She tilted her chin, jerking her head so that her ponytail flicked from behind. ‘Let’s hope you do a better job than Pauline.’ These last words seemed charged with scorn.

‘I’ll do my best.’ There was a drop of perspiration teetering on my forehead.

‘Please tell me you don’t drink alcohol,’ she said.

‘Rarely,’ I replied, holding her stare, all the while thinking, It’s none of your business. I’ll do whatever I like.

Marta was pulling on Petra’s arm. ‘Come, Draga, help me get the eggs.’

Petra’s judgement came before they disappeared behind the trellis screen. ‘She’s rather pale. A little scrawny for a Dally, don’t you think?’

I swiped at my brow. Stipan had moved back to his dahlias and was snapping off the dead-heads. Even after that brief encounter I could see that there was something invincible about Petra, that I would have to watch myself around her. I made it back to my room before the tears took over. Tata was to blame and I would never speak to him again. I reached for my dragi’s vest and wrapped my arms tight around it as though cuddling him, wishing myself back into his arms.

MARCH

I peeked around the kitchen doorway. Roko sat at the dining table, a block of stone, reading the newspaper and eating his breakfast. I pierced his stiff back with my dagger stare. He can’t have been blind to my distress, but over the past two weeks he hadn’t said a word to reassure me. We could be in the same room and he’d stare right through me as though I were a genie who had magically appeared to prepare his food and scrub his clothes. I leaned against the doorframe, sapped of all energy. If things don’t improve, I’ll get out and take my pin money with me. Why should I pander to him? I’ve had enough of being told what to do. But even as these brave thoughts formed in my head, I knew I was stuck: a young girl with no money and no contacts other than this family. Even if I could return home I’d be viewed as fickle, ungrateful for turning down the luxuries, foolish for turning down a better way of life. I thought back to my parting limpet-like hug with one of the local ladies who had travelled on the same ferry from Vela Luka to Split, the one who made sure I boarded the right bus to Belgrade airport. ‘You’re one of the lucky ones,’ she’d said, matter of fact, prising herself away.

Roko pushed himself to standing, and I scrambled, peeling myself off the doorframe to busy myself in the kitchen. The fact he hadn’t communicated his expectations added to everything else I felt unsure of in this country. A man’s gruff voice on the radio taunted me as Roko passed. At times, that small brown box with its leather pinhole cover had been my only companion, but now I felt an urge to throw something at it, to silence the static. I snatched up Roko’s packed lunch and crossed to the dining table, slapping it down.

Back in the kitchen, the monster stared back at me. At least this was one thing I had conquered. Not that it was any consolation. How much had Tata known about what I was coming to? At the time I’d been too incensed to ask questions, too bewildered when he shouted his decision at me in December, the same time that our sermons were filled with ‘forgive and forget’. If my dragi and I ever had a daughter, or a son for that matter, I would never restrict their opportunities or take their freedom away. I would teach them to make good choices so that they didn’t end up like me, compromised, having risked everything. Perhaps I should be grateful: it was clear that Roko was hell-bent on his own plan and even if it was Marta and Stipan’s idea to snaffle me, a nice Dally girl, then at least their son was uncooperative.

He passed by to collect his lunch and slammed the porch door as he left. I thumped my fist on the bench. Katastrofa! No manners, not even a thank you. I waited until he’d swung off down the driveway on the black bike with its rusty handlebars, then crossed to the table, slumping down beside his dirty dishes and pulling the envelope from my pocket. It had arrived the week before, my first letter from home. I’d been carrying Mama around with me ever since, rereading her words and savourin

g the sound of her as though willing her into the room. This was my real Mama, not the distant Mama I’d left behind. She had news about Josip, Mare and the newest member in our family, baby Jakob, about my naughty goats, and our annoying neighbour, and my friend Nada.

I lay my head on my forearms and let my sadness wash over me in waves. Why hadn’t my dragi written? I’d sent a letter most days. Surely he must have received at least one by now? I ached for his reassurance, to know that he was coming to get me. The Dally picnic on the weekend had been the final straw. While I’d enjoyed the familiarity of the Mass, I’d hung back afterwards, unsure of the games they were all playing, and feeling on show as though judged by my own people. My insides had felt like cotton wool and I’d stood to the side, sizing up what the girls my age were wearing and how they wore their hair. They all seemed to know each other — and worse, they all seemed to prefer speaking English. Marta had pushed me towards some annoying older women, the only ones who seemed happy to speak my language. They drilled me with endless questions: who did I know from home, who was I related to? I felt like screaming, ‘What does it matter? Can’t you see I have to make friends here?’

‘Good morning everybody!’ I jerked up my head and stared at the radio on the mantelpiece. It was Aunt Daisy, the lady I’d discovered on my first morning who always entered the room at nine a.m. with her cheerful greeting. I’d got into the habit of keeping her beside me wherever I worked and letting her barrage of happy words wash over me.

‘Come on, girl,’ I muttered, pushing back my chair and shaking my head to clear the mess, annoyed at myself for wallowing. I must have been sitting there for at least half an hour. One of Mama’s favourite sayings was back and I forced a smile. ‘Life’s for the living. Tears are for the dead people,’ I muttered, mimicking Mama’s voice. ‘Get yourself moving.’

The clothes were already soaking in the copper, and I placed the radio on a shelf in the wash-house. There was something about Aunt Daisy’s voice that wasn’t intimidating, and while I still understood so little of this strange Engleski tongue, I challenged myself to recognise at least some of her words. Each day, with Aunt Daisy’s help, I was understanding a little more and recognising words from my school days. I stirred the washing with a big stick. Aunt Daisy chattered while I lifted the clothes then rinsed them in the concrete double sink to the side. I thought about Mama bent over the bath at home with her washboard, how I’d travelled half a world away and ended up with the same chores. I twisted the clothes to wring out the water. At least some jobs were easier here — having a copper connected to electricity, for one — but still I felt cheated.

When I stepped onto the porch with the loaded wicker basket, the rattle of the cicadas was almost deafening. Would the lady next door already have her washing out? I’d seen her a few times but I’d felt too self-conscious to introduce myself, embarrassed about my lack of English. I paused, taking a deep breath, always hoping for a whiff of the sea. I hadn’t realised how the smell of a place could ingrain itself, how desperate I would be to hear the sea, to smell it, and to feel the salt stinging my skin. If only Roko lived in one of the seaside suburbs Stipan had driven me to on my first weekend. His pride had been so obvious when he’d shown me the Tamaki seawall and explained how he’d helped construct it all those years ago. I’d been more intent on drinking in what was behind his stone barrier, imagining that sea washing over me.

She was there, pegging up the last of her washing, tiny beneath her line laden with sheets and towels. The call of the cicadas now seemed like a congratulatory cheer. She must be cutting corners, I thought — her washing couldn’t possibly be as clean as mine. I stalked over to my own monster and untied the knot. The timber arm creaked and groaned as I pulled on the rope, lowering the beam until the line was within reach, then tied it off again. I’ll have to be more organised, I lectured myself, jabbing the pegs on the washing.

‘Hello there!’

I straightened, holding a pair of Roko’s Y-front underpants by the waistband. She was looking over the fence, her forearms resting on the top, beckoning me over. I dropped the underpants in the basket and crossed the lawn to join her. She looked immaculate: lipstick even at that early hour and not a hair out of place. I smoothed back my hair, certain it must be like a bird’s nest given how I’d been raking my fingers through it earlier.

‘Hello, I’m Joy,’ she said. Her hair was like fine strands of beautiful copper-coloured wire, moulded into a stiff bob and framing her face.

‘Jela,’ I replied, my hand at my chest, determined to keep my voice strong. It struck me how she was a little like my friend Nada — her compact features, her tidiness.

She rattled off a string of words I had no chance of understanding. She must have noticed my blank expression because her hand went up like a stop sign. ‘Woah! Okay,’ she said, smiling. ‘Slowly, slowly.’

There was something about the way she scrunched her nose, and the freckles peppering her face, that lent her a mischievous look. It was as though she was transformed into someone younger, less regal. I hoped she might be the type who didn’t take herself too seriously. ‘Polako, polako,’ I said, signalling downwards with my palm and grinning, hoping she might see that I too had a sense of humour. That I would be fun to get to know.

‘Welcome,’ she said. ‘Your country?’

‘Yugoslavia,’ I said, feeling proud to have understood her words.

‘Dally? Like Roko?’

‘Yes.’ I nodded, my mind racing to think of something else to say, to keep this conversation going. ‘Lijep dan.’ I pointed to the sky. ‘No. No.’ I waved my arms skywards, frustrated I’d slipped back to Croatian. ‘Bootiful!’ But as soon as the syllables left my mouth I knew they sounded wrong.

‘Yes,’ she said, nodding enthusiastically as though wanting to reassure me, her hairdo sitting fixed like cement. ‘Nice . . . dry . . . washing . . . today.’ She sounded out each word, gesturing from her line to mine.

‘Šampion,’ I said, opening my palms as though handing over a prize. She looked puzzled, and I pointed at both our washing lines, the English words suddenly there. ‘Number one!’ I said, giving her the thumbs-up sign.

Joy rewarded me with her own thumbs up and clapped with delight. ‘Okay. I can teach. Help you. With your English.’

‘Yes.’ I nodded, feeling fit to burst. ‘Yes, please.’

She reached over the fence and we shook hands as though making a business deal. A baby cried out close by.

‘My little boy,’ Joy said, dropping my hand. ‘Bye, Jela. See you soon.’

Her baby was sitting in what looked like a sling on a metal frame. He was throwing his arms about, jiggling and squawking. My eyes pricked with tears, memories of my little nephew Jakob, and Antica’s little Luci. When Joy turned back the child was on her hip and seemed calmer. She waved before disappearing down a narrow pathway to the side of her white house with its cheerful red roof.

I crossed back to my line with a buzz of energy. This might be the start of a new friendship. I’d never had to make new friends before: there had always been people who had been part of my life from the start. A fantail danced close, flitting from the fence over to the line and back again as though dancing to the cicadas’ tune. It fanned its tail, flashing its white underside. I untied the rope and hoisted the line. Roko’s washing soared high like my own trophy.

Much later that afternoon there was a knock at the front door. Had I heard right? It wouldn’t be Marta: whenever she came she would barge in unannounced. I opened the door a notch, hoping it might be Joy from next door, but it was a man and a woman. He was smartly dressed in a dark suit and grey felt hat and she was all in navy, hanging back as though lurking in his shadow.

The man stepped forward.

‘Hello?’ I said, almost a whisper.

He responded with a torrent of words and I shrank back as the woman pushed forward, tapping him on the shoulder. She carried her handbag like a shield, looped over her arm and clos

e to her body. From it she dug out a photograph. ‘Here,’ the man said, thrusting it at me. ‘Pauline. Our sister.’

That name. I held the thin picture with both hands, focusing on keeping my face calm. I was on the verge of uncovering Roko’s secret, one I was certain he would be furious I’d been privy to. I held it to the light, making sure to inspect it properly, heart pounding in my chest. There she was. Roko’s mystery wife. They were lounging on the sand in front of one of Stipan’s stone walls. Roko was perched on his side facing in towards Pauline. She wore a striped swimsuit cut straight across the bust with a halter strap. A pretty face, heart-shaped. She wasn’t stick thin, but neither was she scrawny — a little slimmer than me. Roko was puffing out his chest, his smile confident, a proud rooster. Pauline had her leg cocked towards him, and it didn’t take much imagination to see how they felt about each other. My face turned to flames. It seemed that Roko was staring at me, challenging me, making me think about the times I’d seen my dragi like that.

‘Come.’ I thrust the photo back at the man, turning to hide my embarrassment. I ushered them down the hallway towards the end room and gestured for them to sit in the easy chairs.

‘Thank you,’ said the man, motioning for me to go first.

I felt proud that I’d taken charge and squeezed past them to sit on the window seat. The man twisted and placed his hat on the dining table. The woman sat staring at her handbag that was balanced on her lap as though it contained something heavy. She coughed a little, shifting about and gripping the hooped handles. The man leant towards me, his hands clasped. A new thought grabbed at my insides. Do they think I am Roko’s new woman?

‘Justine and Peter,’ he said slowly.

‘Gabrijela,’ I replied, feeling their stares. Their judgement. ‘I am house lady. Helping Roko—’

The Telling Time : A Historical Family Saga

The Telling Time : A Historical Family Saga