- Home

- P. J. McKAY

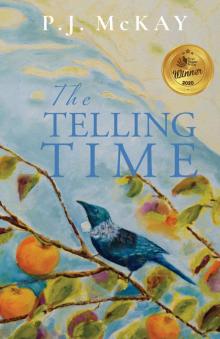

The Telling Time : A Historical Family Saga Page 15

The Telling Time : A Historical Family Saga Read online

Page 15

‘I just wish . . .’ Luisa can guess what Mum’s thinking. The same topic that’s caused so much heartache over the last nine months, ever since Luisa started planning her trip. The silence settles between them, a slow simmering stew of unanswered questions.

‘Don’t look like that, Draga. I’m not the only one to blame.’

Luisa thought she’d kept her face expressionless. She wants to steer clear of all that. ‘Don’t be silly,’ she says. ‘I’m disappointed in Mike. I’m not thinking about you and Uncle Josip.’

‘That’s okay then,’ says Mum, still huffy. ‘But you know I feel guilty the way things fell apart. You can never understand.’

Luisa’s frustrations from the past weeks threaten to boil over — Make me understand, then — but she clamps her mouth shut. What’s the point? It’s difficult walking this precipice. Why is it with Mum that she finds it hardest to contain her anger?

‘If I could change things I would,’ says Mum, heaving herself out of her chair and heading towards the kitchen. ‘But that brother of mine will never understand.’

Luisa lets her go. Bex stepping in was a lucky break. If she hadn’t, there was every chance Mum might have pushed to join Luisa earlier rather than stick to their agreed plan: her parents will join Luisa in a year’s time once she’s done the travel she wants to do and is settled in London with a job. Luisa’s promised that they will all travel to Korčula then and she won’t pressure Mum to contact her family. It’ll be fun, she reassured Mum. Just let me do my own thing first.

Mum bustles about in the kitchen and Luisa reminds herself of the need to tread carefully, to not jeopardise what’s been set in motion. Only then will there be a chance to pave the way for a reunion, to fix things without Mum mucking things up. Two more weeks, just two more weeks.

AUGUST

Tuesday

Yugoslavia feels so close now. It shares a border with Greece, and Samos is an island just like Korčula. Mum so often described the colours back home — the vibrant blues, pinks and greens — and these same colours are here, colliding with the way of life based around the fishing villages. There’s the Mediterranean flavours too, lashings of olive oil and garlic, the way Mum cooked at home. Luisa can picture herself on Korčula now. She can almost taste the country she’s waited so long to experience. Earlier in the day, she and Bex made the most of the morning cool, visiting the Roman ruins at the temple of Hera. Now, with the sun blazing, they while away their afternoon on Kokkari beach. Tomorrow they’ll catch the boat to Athens.

It’s only the tourists who remain, lizards lazing on bright blue sun-loungers strung out along the beach. The row of umbrellas behind them, matching blue-and-white striped petals, are like exotic poppies in full bloom. The locals have retreated indoors, except for the beach hawkers. Bex lies on her stomach reading her book. Her cute turquoise bikini she picked up in Turkey is a perfect tonal match with the sea. Luisa is in her sleek black one-piece. She wishes she could borrow Bex’s curves to fill out a bikini. Bex jokes that a string-bean body is preferable to a perfectly condensed pear, but Luisa’s not convinced. The sun is a warm, weighty blanket on her back and the steady swish-swish of the sea tumbling forward and back over the pebbly shore merges meditatively with the hum of conversation drifting along the beach. Only the occasional shriek from a seagull, or caustic shout from a beach hawker, pierces the relaxed mood.

Luisa will go for another swim later. Right now it feels too exhausting: even reading saps her energy. It’s been fun getting caught up in Bex’s bubble, and easy, given the condensed time they’ve spent together to fast-forward their friendship to a place that would ordinarily take Luisa much longer. Some of the confidences they’ve shared — embarrassing drunk moments, losing their virginity — are the kind Luisa often hesitates to disclose. The opportunities for talk have been endless, on buses and trains, while walking and exploring new places, and it’s a skill Bex has honed. There’s an energy about her, a directness that’s refreshing. Luisa’s joked lately that Bex could be her secret weapon: meeting new clients at work has always been the ‘must try harder’ point on her performance review. There’s been the odd niggle — Bex does like getting her own way — but it hasn’t been a major and mostly Luisa’s been happy to go with the flow.

The closer they’ve drawn to Yugoslavia, the more Luisa has been thinking about Uncle Josip and how maddening it is that Mum’s made this so difficult for her. Until she finds his reply at her next poste restante address in Belgrade she won’t relax.

Bex’s lounger creaks and groans and Luisa drags her head upwards to squint across at her. Bex is sitting now, replacing the cap on the sunscreen tube. Luisa’s hardly broken a sweat but there’s a sheen coating her arms, intensifying the colour of her tan.

‘Luisa, we need to talk.’

‘What?’ Luisa says, the effort almost too much.

‘I feel terrible . . . but I have to change my plans. Go straight to London from Athens.’

Luisa pitches up and her own lounger squawks. How can Bex be so selfish? There’s been no hint of this. Just the other day when they were posting the letter to Uncle Josip Bex said how much she was looking forward to Yugoslavia.

Bex’s head is cast down with her arms wrapped around her knees. The afternoon sun feels overbearing.

‘What do you mean?’ Luisa tries to keep her voice calm but inside she’s churning.

‘I need to be sensible. I’m nearly skint and September’s the beginning of the school year.’ Bex’s voice is clipped.

Luisa’s thoughts race back to Mike. He’s the reason Bex is here. That they’re even having this stupid conversation. Surely she’s not going to be let down again. Bex signed up. No one forced her. It’s rich to change her plans now.

‘That’s bullshit, Bex! You won’t even need money when we’re with my rellies.’ Despite the familiarity they’ve gained, Luisa has been cautious about holding her tongue to keep the peace. She can’t believe she’s venting now. A couple who were happily canoodling glance across. Is Bex even blinking behind those big white sunnies? Luisa can’t tell. She looks rigid, as though by moving she’s afraid she might cause more upset.

‘I thought you’d understand,’ says Bex. ‘You know money’s tight. And we’re so close to your rellies now, it’s not as if you’ll need me.’

Yeah, right. Luisa’s head is spinning. It’s great to be logical when it’s me you’re letting down. Luisa’s been so careful to keep their spending in check: sharing meals, limiting alcohol, sticking to a budget that would work for Bex. A scraggy cat approaches and Luisa flicks her hand. It slinks off towards the shoreline, taking an exaggerated path as though knowing to give them a wide berth. What hurts is that Bex has conveniently ignored the one thing that’s most important to Luisa. Only a couple of weeks back she’d opened up to Bex, really opened up: her worries about meeting her relatives and whether they’d accept her; her quest to understand why Mum’s father sent her away. Luisa’s stomach churns. She and Bex have been so comfortable with the routine of moving from place to place, country to country. She pictures herself sitting alone in a hostel, asking directions, seeing the sights and having no one to share them with.

‘It’s not just about the money,’ says Bex, cutting in to Luisa’s thoughts, her head resting on her knees.

‘Then what else?’ says Luisa.

Silence. Just the swish, swish of the waves, creeping onto the shore.

‘Come on. We had a plan. It feels like you’re ditching me. Looking after yourself!’

The couple are openly staring now. Luisa glares at them and they hunker back down.

‘I’ve had enough. Want to unpack. Start living normally.’ Bex’s voice, which is usually so forthright, sounds tiny.

‘How can you say that? It’s just an extra month. You can unpack at my rellies. Shit, Bex, you owe me.’ The couple are still leaning on every word but Luisa doesn’t care. ‘We’ve done all the things you wanted. It seems convenient to take off now.’

‘It isn’t what I want, but I have to be sensible.’ Bex rubs at her face, eyes still hidden behind her sunglasses. ‘I’m worried about London. How I’ll cope. If I get there before the school year starts I’ll have the best chance of finding a job.’

‘But the school year’s always started in September.’ Luisa only just stops herself from throwing her hands in the air. ‘How come this wasn’t a problem when we were planning?’

In slow motion Bex swings her legs to sit facing Luisa. She removes her sunnies and her face is all angles, like cut glass. ‘There’s something I need to explain, but it’s something I haven’t told anyone else, not even Niamh. Can we walk? It’ll be easier to talk.’

The vulnerability on her face reminds Luisa of the spidery crazing lines on Baba Marta’s old china teacups. This is important, Luisa thinks, scrambling to stand, as though she’s about to be let in on the real Bex.

They wrap and tie their sarongs and bundle their gear into daypacks. Luisa thinks of popped balloons. She feels guilty, as though she’s failed Bex, missed the signs. Along the beach the line of lizards are as they were. The inquisitive couple have slotted back like spoons, their backs turned.

‘Hey, you. I’m sorry.’ Luisa pulls Bex into a hug. ‘Don’t worry. We’ll work this out.’

Bex is quiet again as they wander up the beach. Luisa’s eyes smart and she’s thankful for her dark glasses. The crush of small pebbles is replaced by the clipped flip-flap of their jandals on concrete and Luisa slows her pace, flicking her arms to shake out the tension. She’s like her dad on a mission: arms swinging like rotors, fists clenched into tight balls.

Further ahead two older Greek men amble, deep in conversation. One has a newspaper folded under his arm, the other holds a laden shopping bag. A bougainvillea splays over a wall, a blast of shocking fuchsia. Bex still hasn’t said a word. A woman sits on a wide step in front of a turquoise door, shelling some kind of nut. Her hair is a shock of white, contrasting with her black dress. She glances up, her square-cut jaw set.

A dog, the colour of Russian fudge with a bushy tail, crosses the street and pads alongside them. They’ve grown accustomed to this escort service, available most mornings and evenings when it’s cooler and the dogs have the energy to shake themselves up from the patches of shade they’ve been slumbering in. This dog has broken the mould.

‘Hello, you,’ says Luisa, grateful for an excuse to speak. The dog slows, and Luisa wonders if its eyeing the hill ahead, weighing up its energy levels. It turns and slopes off.

‘No staying power,’ says Bex, staring after the dog. Luisa wonders if she’s registered the irony but then a wry look crosses Bex’s face. ‘Come on, this hill’s not going to beat us.’

Bex strides off and Luisa is left feeling like one of her school children. She is already partway up the rocky slope before Luisa catches her again.

‘You’re probably wondering why I chose to come away with you.’ Bex doesn’t give Luisa the chance to answer. ‘The chance to travel felt like I’d been gifted a solution at just the right time. I admired your determination to follow your dream. You seemed so sure of yourself. It was the kind of stuff I wanted to see in myself. What I’d been talking to the counsellor about.’

A counsellor? Niamh described Bex as the most upbeat and motivated person she knew. Until now, Luisa’s had no reason to question that.

‘Amazing what you can hide,’ says Bex, as though sensing Luisa’s confusion. She pulls ahead again, scaling the hill like a mountain goat. Luisa tries to ignore the burn in her lungs as she picks her way up, still trailing behind.

‘Towards the end of last year I realised I needed to face up to some things about myself.’ Bex turns to offer her hand and pulls Luisa up to stand on the ledge. Luisa is relieved when Bex collapses onto a bench seat tucked into the hillside at the rear.

‘There’s so many things I’m not proud of. Everyone jokes about my string of boyfriends, me included, and some of the choices I made were shockers. I’ve been using guys like a crutch, bandaging over what I couldn’t face. The counsellor helped me understand that it goes back to Mum and Dad’s divorce. Hardly rocket science.’ Bex grimaces, and counts off the reasons on her fingers. ‘Only child. Dad distancing himself. Mum so distraught I couldn’t trouble her. Having a boy at my side saved me from focusing on my troubles. After so many years all it’s meant is that I’ve wound up feeling used and disconnected from who I am. By the end of last year I’d backed myself into a corner. I’d lost the essence of what I really wanted from life.’

Luisa puts her arm around Bex’s shoulders, drawing her close.

‘Being able to come away with you and leave all that behind, felt positive, a step forward.’ Bex leans her head on Luisa’s shoulder. ‘But I can’t ask Dad for more money, and I don’t want to fail or make things harder than they need to be. I thought I’d be okay, that I’d be happy to wing it. I was looking forward to breaking free of all the routines, but I guess it’s something else I’ve learnt — I’m not much of a risk-taker.’ Bex lifts her head and frowns. ‘Unless it’s men we’re talking about. My counsellor would say, be kind to yourself. I need some security, and teachers don’t have the luxury of a big pay-cheque.’

Luisa turns and focuses on the view. The difference in what they earn has come up a number of times already, and she knows to steer clear of that topic. Even with Niamh she’s never been comfortable, but it’s not something she can solve.

‘You’ve been through the mill,’ she says. ‘Hey, I understand, honestly.’ She rubs Bex’s back and they both gaze across the mix of flat and terracotta rooftops towards the azure sparkle. Luisa drinks it all in. For Mum, New Zealand must have felt so foreign.

‘I’ll definitely miss these stunning views,’ Bex says eventually. ‘That sea’s like a jewel.’

‘Easy to take for granted.’

Bex nods in reply, seeming content to sit and absorb it all. Luisa wonders what she’s thinking. Most likely the obvious, that London will feel a million miles from all of this. A few clouds stretch like soft, twisted scarves along the horizon, tone upon tone of muted coral mixing with the blue sky. Luisa pictures her mum, hands on hips, pontificating the way she does. Bog će ti pomoći — find the inner strength. Luisa grins. God’s got a lot of work to do, but of course she’ll cope. She’s made it through law school, succeeded in a high-demand job, and she’s comfortable with this travelling drill now. Mum travelled to New Zealand by herself, after all.

She sneaks another glance at Bex, whose face is turned to the sun, her sunnies a white figure-eight racetrack perched across her nose. There’s still a niggle, though. How much money has Bex got left? If she doesn’t have a buffer, arriving in London by herself could also be madness. The irony of Luisa’s letter to her parents isn’t lost: We’re taking a boat across to Italy, then winding our way up through Europe, to London. Not a lie, just a small shift in latitude to the left. Perhaps she should ditch her plans and travel to London with Bex — make sure she’s settled? She can always visit Yugoslavia later. But then, how responsible should she feel for Bex? She’s already made concessions. At what point does she stop owing her? Mum’s back in her head: Life is full of compromises. Perhaps there is a better way.

‘Hey, you. Being young isn’t always about being sensible.’ Bex rewards her with a cheeky grin. It’s the same advice Bex has flung her way over the past weeks. ‘I don’t want this to sound selfish, but how would you feel if we pooled the money we have left? I’ve still got travellers cheques and you could pay me back. You know as well as I do that you’ll get a job. We can re-think things and shorten the trip. Get to Korčula in a couple of weeks, or however it works best. Just imagine unpacking, and being in a home, experiencing the culture. Take your time, though. You don’t need to decide right now.’

Bex’s forehead creases with a frown. ‘It’s tempting. And I can see why you’re a gun lawyer.’ She quietens for what seems like an age. ‘Okay,’ she says finally, her voice m

ore determined. ‘Can I think about it? But only if you’re sure you don’t mind and I can pay you back. Can’t have you becoming my substitute crutch.’

Luisa pulls her close. ‘Of course I don’t mind. I’d be stoked. You should know that.’

Bex wriggles backwards to look Luisa in the eye. ‘I’ll let you know tomorrow. You know I’d be gutted to miss out.’

As they pick their way back down the slope, the sky turns a burnished orange, the scarves now transformed into licks of fire. Luisa feels she may have just negotiated a minefield — that the balance might be restored. Of course she could survive by herself, but it wouldn’t be nearly as much fun. Besides, if Bex does agree, the added bonus will be that Luisa can help settle her in London later. Keep an eye on her.

AUGUST

Monday

Six days later, needing to escape the cauldron of Athens, Luisa and Bex are in Thessaloniki. Their backpackers is close to the beach, away from the city centre. They wander along the sea wall looking for a taverna to dine at and a waiter pounces, greeting them as though they’re the catch of the day. He leads them to a corner table set with a checkered green-and-white cloth overlaid with a thin plastic sheet secured around the table legs by an elastic band. The plastic cover allows for a quick turnaround of the tables — the Greeks are slick at this — but tonight they won’t be rushing. They need time to finalise their plans for travelling into Yugoslavia.

The waiter hands them the menus and lights their candle in the iron holder before racing off to chase down some potential patrons who have had the gall to pause at his blackboard menu then wander on. Bex laughs when he leads them back. ‘Got ’em! They’re masters at it, aren’t they?’

The Telling Time : A Historical Family Saga

The Telling Time : A Historical Family Saga