- Home

- P. J. McKAY

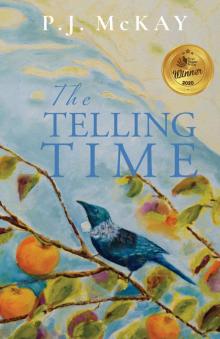

The Telling Time : A Historical Family Saga Page 11

The Telling Time : A Historical Family Saga Read online

Page 11

‘You okay?’ Roko’s right arm was bent out the window, his hand guiding the steering wheel.

‘Yes,’ I said, smiling. ‘Always happiest by the sea.’

Roko stared ahead and we drove in silence. I gazed out the window at the city bursting with colour. Joy’s summer had arrived. People were strolling along the waterfront, some with pets. Families gathered on picnic rugs on the beach, or in the parks — children running, chasing balls, making sandcastles, some out swimming. Perhaps I should have brought my bathing suit? No. The embarrassment of getting changed. How would he look at me?

I focused instead on all the boats making the most of the slight breeze. The harbour was a playground of sails, and I felt that same deep-seated ache whenever I remembered the sights and smells of my homeland. It felt like such an age and I worried what I had forgotten, whether my memories were true.

We wound our way towards St Heliers, past the stone sea walls that bore Stipan’s signature, his special pattern of rocks. I’d come to think of them as his stake in the ground, his claim on foreign soil, in this country he now called home.

I was pleased I’d had the sense not to wear nylons when, at the beach, Roko suggested we take off our shoes. While he found a safe place for them up by the bank, I waited on some flattened black rocks, fixing my eyes on the water, drinking it all in. The rocks were pitted with crevices and small holes, rough under my feet, reminding me again of home.

‘Beautiful, isn’t it?’ Roko called out. He was flapping his arms at a seagull that was strutting towards our shoes. The bird swooped off with an angry caw.

‘Meanie,’ I called, watching him pick his way back over the short flow of rocks.

I nudged him with my hip when he drew alongside. He held out his hand and I took it as though this was the most natural thing, feeling as free as the bird circling above us now. We stepped onto the sand and wandered down to put our feet in the water. The waves crept in, quiet little rolls, retreating with just the gentlest of tugs. I dropped Roko’s hand and ran ahead, splashing and kicking the water into a spray. He picked up some stones and skimmed them across the flat water. When I joined him again, I threaded my fingers through his and we walked on towards the cliffs at the eastern end of the beach. There was no need to fill the silence with talk but every so often he reassured me with a smile.

A few families were gathered on picnic rugs at the sheltered bay. Buckets, spades and beach paraphernalia strewn about. ‘Achilles Point’s just around there,’ said Roko, pointing past some children who were clambering over the rocks to the side. ‘If the tide’s right, we can get around.’

We picked our way past the children, some bent low inspecting rock pools. We needed to take care because some of the rocks were sharper there. I pointed towards some small caves up ahead. ‘There were hundreds of caves in the hills around Luka. Exploring them was one of our favourite games when I was younger.’

‘Mountain caves?’

‘I guess. They were set into the steep cliffs. We tried to find a new one each time. Who knew what you might discover. Sometimes it was things left from the war.’

‘Like guns?’

‘Occasionally. Josip found one. But more likely it was scraps of ammunition. Sometimes old clothing, or an empty food can.’

‘We made do with sticks shaped like guns,’ said Roko. ‘Dad always said we were lucky living here. To be honest, I had no idea.’

‘Before coming here, I didn’t realise what we’d gone without. It wasn’t all bad, though, and there’s still so much I love. It wasn’t until I was older that I wanted to escape. I miss it.’ I turned to stare at the sea.

Roko pulled me close. ‘You’re a brave girl, Jela,’ he said, caressing my cheek with his finger.

I could barely breathe. His lonely mole, just below the line of his jaw, twitched as he bent to kiss me; a delicious kiss, a taste of what might be possible. Afterwards, I buried my face into the warmth of his shoulder. It felt like an eternity since I’d been held close like that but I couldn’t relax. Feelings of shame pricked all the way down my spine and I edged away.

‘I want to take you to a secret place for our picnic,’ he said, not seeming to notice my discomfort, his eyes bright like caramel toffee, his expression playful.

He took my hand and led me back over the rocks and along the beach to collect our footwear. I forced my mind back to the present, determined not to ruin the moment again. When he gestured towards the car I stared at him, puzzled, having assumed our picnic would be somewhere on the beach. Roko drove the car up a series of tight bends and no matter how much I badgered him, he remained silent.

‘We’ll walk from here,’ he said, pulling over and flashing me a mischievous grin. From the boot he took a small case and a crimson-and-green tartan rug. ‘We’re off to Dingle Dell. Coming?’ He handed me the rug.

I followed him, ducking my head to squeeze through a gap in a small copse of trees. A gravel path bordered by palms and ferns wound its way uphill; there was a densely planted area either side. I paused to examine a bright green fern frond, pulling it close, intrigued by the tight coil close to the trunk. It was as intricate as Mama’s lace work.

‘Our koru,’ said Roko. ‘The beginning of a brand-new fern. The Maori people say it’s a symbol for life. How life changes but stays the same.’

I nodded, impressed by his knowledge of nature and was about to ask more, to test his know-how on some of the other plants, but Roko was striding ahead, the little suitcase so at odds with his bulky frame. I followed, clutching the rug close, feeling as though I was being drawn into a magical world. It was cooler in there. The sun’s bright disc was no longer in command. Instead, the light was whittled down to threads that pierced the tangled canopy to paint dappled shadows on the path. I had the strong sense that nothing would have the luxury of drying out in that place. The air held a tang of dampness, not an unpleasant smell but one that brought to mind saturated moss, or moisture beads clinging to the undersides of the fern fronds. I was transported back to that cave, to those final moments with my dragi. No! I squeezed my eyes shut, determined to banish those memories, rushing to catch Roko just a short distance ahead.

‘What is this place?’ I asked, puffing a little as I drew closer.

‘Patience.’ Roko turned back and grinned before pushing on up the hill.

At the top, the path opened onto a small grassy clearing that was bathed in sunlight. There was a peep out to the cornflower-blue sea and we were the only ones there.

‘It’s perfect,’ I said, ‘but tell me the story. How did you find it?’

Roko smiled. ‘Dad liked bringing us here. He was asked by some of the locals — men he worked with while building the sea walls — to help with the project of replanting it. It was nothing more than a swamp originally and it’s a place he’s proud of. He also used to say that the view was a reminder of home. I thought you might appreciate it too.’

I dropped the rug and flung my arms around him. Suddenly I didn’t feel homesick and being here with Roko felt perfect. He laid out the rug and unclipped the hinges on the case. Everything was in order: plates the colour of butter and a selection of cutlery with bone handles all held by some leather straps in the lid. A thermos, cups, and containers of food were packed into the base: ham sandwiches, a selection of fruit and thick slices of gingerbread loaf. Marta had thought of everything, even small containers of butter, milk and sugar.

As usual, Roko was intent on devouring his food and we enjoyed our picnic with little need of conversation. When a fantail danced close, landing on the suitcase lid before flitting away again, I confided how I’d thought of those little birds as friends when I’d first arrived, how they were a reminder of the swallows that used to nest in the eaves of our houses at home. Roko smiled and I revelled in this new ease between us. After eating he lazed back on the rug, his arms crossed over his stomach. He reminded me of a contented cat, like Mala stretched in front of the fire. I assumed he had dozed off and for a

fleeting moment considered stretching out alongside him but then cautioned myself, polako, polako. It would feel too intimate, a step too far. My hands felt clammy, and I smeared my palms on the rug as though to wipe away my disgust. I knew so much about the ways of love, or lust, and yet I had lost all sense of appropriateness. Would I ever regain this? Regain my sense of self-worth? That man, in robbing me of my innocence had also thrown away the rule book.

I gazed out to sea, feeling the heat from the sun and forcing my mind towards things I could control. Anticipating telling Joy my news, and writing to Nada and Antica, Mama as well. I pictured their reactions, Mama’s smile. How wonderful to share something positive — to make her proud again.

‘Jela?’

I turned to him, surprised at the strained note to his voice. He was propped on his elbow now but facing away towards the bushes. I leant across to touch his shoulder but he flinched, and I withdrew my hand as though I’d been burnt. It was some time before he spoke and when he did he was still turned away, his back rigid.

‘Does it worry you about Pauline? That I’ve been with her?’

I took a moment to answer, weighing up whether this was also my moment to confess, whether I felt courageous enough. The little fantail danced close and I stared out to sea, knowing I had everything to lose. Even though I would have to broach the subject eventually I didn’t want to ruin this day.

Roko turned to face me, looking worried, as though he was the one needing rescuing. My words spilled out. ‘It makes no difference to me.’ I reached across again, my fingertips feathering his forearm with whisper strokes. ‘But how would you feel if I had stories of my own?’

It was done. I made sure not to draw back, to look straight into those eyes which had often held such sadness, to make certain he understood me, that there could be no misunderstanding. He blinked as though puzzled before hauling himself to sit, shaking his head as if to clear away any thought of me with someone else. Perhaps he thought of me as another problem? Maybe I had shocked him? I inched my arm back, staring at my hands cradled now in my lap as though nursing a bird with a broken wing. His stare felt too intense. I hadn’t felt this exposed since Tata found out about me. Perhaps Roko was no different? Perhaps he thought of me as soiled goods too.

‘You’ve surprised me, that’s for sure,’ he said, after the longest time. ‘Knocked the wind out of my sails. Hadn’t thought you the type.’ He leant over and made a clumsy effort to pull me close, but I shrugged him off, holding his eye, fuming inside. A look of shock crossed his face. ‘C’mon, Jela. Of course it doesn’t matter. I’d be a right arse to criticise, wouldn’t I?’

I snapped my head towards the water, still seething. Not the type! Perhaps he thought I had no spark? That photo — Pauline’s leg cocked towards him, his look, her smile — was I so different? My eyes smarted, my confidence feeling rocked to its core. But how did I want men to view me? What would Roko’s reaction have been if I had been brazen enough to lie beside him?

‘Katastrofa!’ I said, under my breath, swiping my hand out towards the horizon, as though giving that other man a slap across the face too. Again, I begrudged the bubble surrounding me. The thin iridescent film distorting my perceptions, keeping me at arm’s length from the subtleties and nuances of this country. But Roko must realise how difficult my confession was? How could he show so little compassion given what he had been through too?

The sea was blurry now but I continued to stare, furious about life being so unfair, about double standards and how much easier it was for the men. I thought about Branko, my first boyfriend, the one I’d sent packing when he thought he had the right to tell me what to do, to keep me in a box, contained. Tata was the same and perhaps Roko was no different. Surely I hadn’t come all this way, sacrificed so much, to end up with the same small-mindedness? With my dragi it could have been so different. The thought was no sooner out when I realised how warped it was, how that man had twisted my perceptions. I punched my clenched fist onto the rug.

Roko inched closer and squeezed my shoulder. ‘Come here, you,’ he said. ‘Get off your high horse and tempt me with another kiss. I’ll listen to your story properly then.’ He rubbed my back. ‘I’m sorry, Jela. I was an arse.’

I was still bristling when I turned to him. He brushed his lips against my forehead. ‘It pays to be totally sure about these matters,’ he murmured, before kissing me properly.

He asked no further questions. I wanted it to feel right but the magic had vaporised and all my fears which I had kept hidden for so long wrested their way to the surface. I knew it. Of course it was true. This curse was mine to bear, my penance, God’s punishment. And any shot at happiness would always be plagued by it.

We wasted no time in packing up and returning to the car. On the drive home the very air we breathed felt laced with peculiarity. The spell had been broken. Even if there was a chance of me breaking this jinx, I would be a fool not to be cautious about being let down again. Worst of all, I couldn’t erase Roko’s expression of disappointment, the sense that I’d failed him, that I should have been stronger.

DECEMBER

It was my first public date with Roko and my first time at a race meet. I was with Roko’s family, and together we took up several rows near the back of a huge grandstand at the Ellerslie Racecourse. With all the finery surrounding me, I felt nervous, on show, conscious of his family watching my every move as though I might behave differently now that I was Roko’s girl. We were packed into the stand, a sea of hats, our knees at each other’s backs, a riotous ripple of colour, like stacked dominoes poised to topple forward down to the race track. Simun had told me earlier in the week that he would be coming with his family. Most of Auckland must be here, I thought, scanning the stand, grateful for Joy’s advice: It’s a day not to miss, a social event on the calendar — everyone will be dressed to the nines.

I was so proud of my new cream shoes with the smart bows that Joy had helped me pick out with my saved pin money. She would be in the crowd somewhere, enjoying a flutter. I searched the sea of faces again, desperate to catch a glimpse of her, thinking how Mama would love to be here. If only I could transport her, even for a day, and see her eyes open wide like saucers. There was one face I didn’t want to see. I still worried that my luck was about to run out, that the curse was real. I’d only seen Sara once since Joy’s party — at Mass, where she had ignored me. One day at a time I reassured myself, polako, polako.

Roko was seated directly behind and I turned, aching for a smile. His nose was buried in his race book. Petra and Marta chatted at the end of my row, Petra waggling her hands in her white gloves. She wore a shiny black-and-white polka-dot dress, one I’d never seen before. Marta was all in red, her new hat with its thin rim was like an upturned saucepan. A single ruched flower, the size of one of Stipan’s dahlias, was stuck where the handle might have been and it bobbed about as she talked.

Hana, in her fresh mint-green sundress paired with white gloves, sat beside me. I thought those gloves so luxurious, something that a queen might wear. Having never imagined myself owning something so frivolous, I now coveted them, secretly adding them to my wish list. Tracy, Zoran’s mystery girlfriend, sat on the other side. I’d been informed by Hana that she was just two years older than me, but she seemed sophisticated and much older than that. Her short orange shift dress, one like Joy’s, was sure to draw comment from the rest of the family.

As though on cue, Hana leaned close. ‘Take a look at Tracy’s hairdo. What do you think?’

‘Very modern,’ I said, keeping my answer neutral, trying to read Hana’s face.

‘Enjoys being the centre of attention,’ said Hana, nodding as though to affirm her knowing look. ‘No wonder Zoran kept her hidden for so long.’

I glanced behind again. Roko’s nose was still buried. Like all the other men in the row, he was dressed in his suit. Stipan wore his smart felt hat and even Hana’s two young sons were like mini businessmen with their grey serge shorts ti

ghtened with fabric belts, shirts tucked in and grey socks pulled up to their knees. Petra’s three daughters were all dressed in pretty party dresses teemed with white ankle socks with lacy frills. Both Kate and Nick had joined us. Kate, in her smart lemon-coloured jacket and skirt, had one of Petra’s girls either side of her.

Tracy nudged me. ‘Marta’s the stop sign and Petra’s the conductor,’ she whispered. ‘Won’t get much past them.’

I stifled my laugh with my hand. Secretly, though, I coveted Marta’s hat. My head felt so bare and plain, and I had already decided a hat would be my next purchase, before the gloves. I flexed my ankles remembering my new shoes, a perfect match for my navy striped dress.

Roko tapped me on the shoulder. ‘You okay?’ he mouthed, beaming when I nodded yes.

I turned to face the track again, feeling lightheaded. It was a month since our picnic, but I still sought his affirmation, his assurance that he hadn’t reconsidered. I found it impossible to push aside the fear that I was a passing convenience, a fad. If the way Roko kissed me was anything to go by, then ‘soiled goods’ couldn’t have been further from his mind, but then my dragi had been no different. It was obvious Roko found me confusing at times. He couldn’t hide his hurt expression when I put up the shutters and closed him out. I had no warning when these feelings might strike to ruin a tender moment — me turning away, becoming matter-of-fact — and every night I prayed that Roko would focus on the beautiful moments, the times when I felt free to be myself and send my fears packing, the times when our love felt right.

All the same, I knew it was madness not to have a contingency plan. The niggle about how much his family knew of my past life was a constant worry, and with the prospect of Sara still lingering close, I’d been trawling through my options, even though the thought terrified me. I could trust Joy to help me find somewhere else to live but getting a new job would be difficult. If it came to it, though, I would have to find a way.

The Telling Time : A Historical Family Saga

The Telling Time : A Historical Family Saga